When Tara Gujadhur first arrived at Luang Prabang, Laos in 2003, she found a wealth of different cultural communities, but little information about them that was accessible for visiting tourists. These communities also experienced a disconnect between their traditional cultural practices and modern-day lifestyles.

Today, as the co-director of the Traditional Arts and Ethnology Center (TAEC), Tara manages programs that help indigenous communities of Laos thrive, by providing tourism-based livelihoods and protecting their intellectual property rights, among others. We caught up with Tara and asked her about TAEC, their ongoing work, how they survived the pandemic and how their community stakeholders are facing the future without fear.

I’m aware that that you started the Traditional Arts and Ethnology Center (TAEC) in 2007. Could you take me through its beginnings – what spurred you to co-found it and build relationships with local Lao communities?

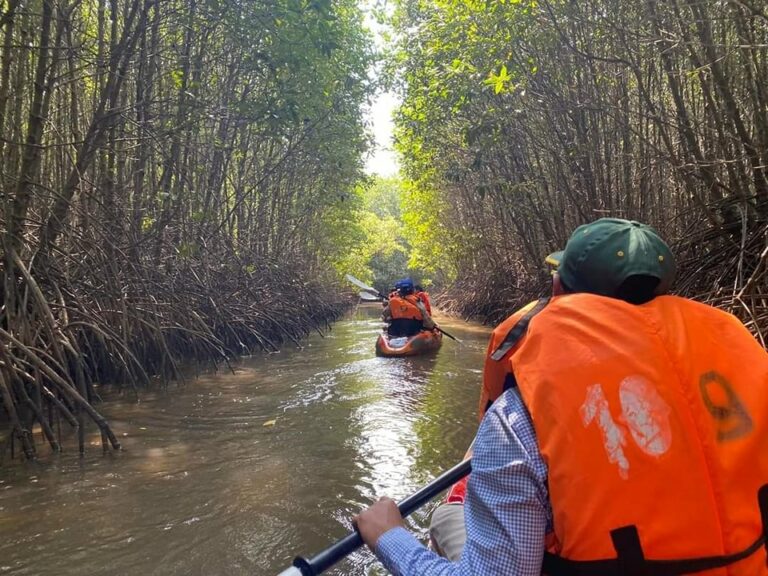

I came to Laos in the end of 2003 to work for SNV, a Dutch development agency. For three years, I was based at the provincial tourism department to advise them on sustainable tourism development. That involved going to a lot of ethnic minority villages around Luang Prabang province, developing community tourism activities and new attractions.

My background is actually in anthropology, so I was really curious about all of these different cultures, but felt that people were not understanding them, or recognizing that they’re even there.

When I finished my contract with SNV, I had really fallen in love with Luang Prabang, and decided to start TAEC. My co-director Khoun [Thongkhoun Soutthivilay], she was actually the collections manager at the Luang Prabang National Museum, so she had the museum background. My background was on community outreach, research, anthropology and ethnology.

So together we decided to set up TAEC; the idea was just to promote more understanding and celebration of the ethnic diversity of Laos for Lao people, and for foreigners who visit the country – just to make that information more accessible to a wider audience.

On the Internet, Lao culture is getting a little more exposure. In this extremely online environment, do you feel the mission is still relevant or even more relevant now?

Yeah, that’s a good question. I would say it’s still relevant. More rural communities are getting more connected to the ways of the West, but they are also changing as well. Their cultural identity is shifting and evolving. I think, in our rush to become more modern, we often leave behind some of our traditions, history and heritage.

So part of our mission is also helping people recognize and appreciate where they come from. In our move to develop, we need to also think about which aspects we really want to hold on to.

At the same time, because people [i.e. tourists] are more curious about the ethnic groups or the cultures of Laos, we want to be able to provide some more of that information as well.

What particular challenges are your stakeholder communities facing, and how is the Center’s outreach helping address those challenges?

I guess there’s one challenge that is probably cross-cutting among a lot of groups – I know some Tai Dam communities in Houaphan, they’re particularly facing this.

A lot of young people from the community are leaving the community to seek higher education, which is great. Some of them are working as migrant labor in Thailand. Those are all great livelihood opportunities. But what it means is that the transmission of traditional knowledge is disrupted.

In the past, people would be in the village their whole lives. And they would see other people weaving, doing rituals, playing particular traditional games, playing a traditional instrument. That’s how knowledge is passed. It’s not like they go to school; it’s a very organic, informal process. So now, because young people are getting more education outside of the community, it just means that a lot of times, there isn’t the opportunity to pass on the knowledge.

Oftentimes, also, the knowledge is not income generating. It’s just knowledge for the community, for their social and cultural fabric of life. So there isn’t an economic incentive for them to hold on to that.

Through our handicrafts at TAEC, we try to combat that by providing an economic incentive. A lot of young women who are weavers, a lot of times they don’t have the same kind of skills as older people do. But by developing crafts and trying to help buyers understand the incredible work, knowledge and skill that goes into them, and get them a higher price, we’ll make it more likely that they learn how to do it and sell it as a supplementary or primary income.

Did the Center and your communities experience any difficulty during the pandemic? How were you able to to to survive or to thrive through it?

Laos borders were closed for 700-something days. And for a lot of the communities we work with, handicrafts sold to tourists are an important supplementary income source. One of the things we did is pivoting to online sales. Which was tough; we got some sales, but nowhere near the volume that it did through our retail brick-and-mortar store.

One of the things that we’re quite lucky about in Laos is, [handicrafts are] a supplementary income source for Lao people. They’re generally farmers. They’re raising livestock.. So I think we were fortunate in that people didn’t lose all their sources of income. Or they didn’t lose their food security. So people weren’t in really dire straits.

And even for a lot of TAEC staff, many of them went back home to their villages. Because [Lao] people still have a real link to the land, they were able to go back, do more foraging, more vegetable gardening, more rice farming and survive. Everybody just tightened their belts, basically.

I saw that protecting intellectual property rights is a big part of TAEC’s advocacy. Could you talk about the indigenous IPs under threat, and how you guys are helping protect local communities’ IPs?

That’s a flagship issue of ours that emerged in 2019 when an Italian company plagiarized a very small ethnic group in the far north of the country. Honestly, before that, it wasn’t something that was on our radar – it hadn’t really hit so close to home before. But then, through our slightly public battle with MaxMara, we realized how powerless a lot of these communities are to this happening over and over again.

Really big companies, with impunity, can take designs, claim inspiration, utilize it, make very large amounts of money. And this happens almost every fashion season, and communities have very little recourse to act, because there aren’t any good legal protections for traditional designs and traditional knowledge. Big companies can just hide behind the law. And it’s all international, too, so different countries have differing legal issues.

We decided to join the Cultural Intellectual Property Rights Initiative, a network of organizations working on this, to raise more awareness. In April of this year, we had a cultural IP month, to provide more information for consumers on social media.

We’re also working with the government to try to improve the legal framework here too. But it’s a slow process.

You have a background in sustainable tourism, and you’ve lived in Laos since 2003. Based on your professional background, what in your opinion does sustainable tourism in Laos look like?

For me, sustainable tourism in Laos should really meet the needs of the country. You know, it’s tourism that invests in local livelihoods, in local knowledge, that celebrates the people of Laos and their background, that it doesn’t just cater only for the needs of the tourist, but is really a sector and industry that would serve the needs of the people,

So having tourism where as much income as possible goes to local businesses, to local services, to local products, and that would that is respectful as well to local norms and values. That’s what I would say sustainable tourism is.

If you had the chance to dictate policy, what what kind of corrections would you make, to ensure that tourism is more sustainable and resilient?

For me, I always like to see more tourism management and less tourism development. From managing the ticketing to zoning, things like that – it’s all about preparation and recognizing the impacts that tourism can bring, positive and negative; and trying to maximize the positive and minimize the negative.

I think a lot of times there’s a focus on community tourism. Though that’s nice, I think a lot more benefits can come from trying to make the run-of-the-mill mass tourism more locally sustainable, rather than only focusing on more rural oriented tourism.