The “Golden Triangle” still casts a shadow over secluded parts of the Mekong Region. Some 950,000 square kilometres overlapping the mountains of Myanmar, Lao PDR and China were once major producers of opium poppies that fed the global illicit drug trade. Hmong, Yao (Mien), Gasak and Khmu villages in Northern Laos – unable to grow rice on the sloping mountain terrain – had little choice.

The decline of opium production in the Golden Triangle has been driven by government initiatives to switch cash crops away from opium, with the help of “profit-for-purpose” companies like Saffron Coffee.

Today, some 800 smallhold farmers now rely on Saffron Coffee’s expertise and assistance. They receive coffee plants from Saffron Coffee, and are trained on the best way to grow and harvest the coffee crop. The coffee plants are shade-grown Arabica, ideal for planting in forests. Saffron then buys coffee cherries from the farmers; they take over the sorting, roasting, and eventual export of the high-quality coffee that they produce.

We asked Brendan Pont, Saffron Coffee’s manager, to talk to us about the impact their social enterprise has made in Northern Laos – and why the area produces some of the world’s best coffee.

Saffron Coffee actually started with the intention of helping villagers transition from opium to coffee. What was the situation like when Saffron Coffee opened its doors?

David Dale and his wife Tou started the business back in 2006. When they started, Laos, along with China and Myanmar, was part of the Golden Triangle: the largest opium producing area in the world, prior to Afghanistan taking that over. In the early 2000s, governments were running eradication programs around opium. And the initial impetus was, these hill tribe villages lived in areas that we knew would be okay for coffee growing, and they needed to switch over to another cash crop.

Previously, there had been programs to give them coffee, for them to grow and then find a market for themselves. But instead of going down that path, we decided to set up a company that actually created a market as well as provide the coffee plants.

How challenging has it been to transition the villages from opium to coffee?

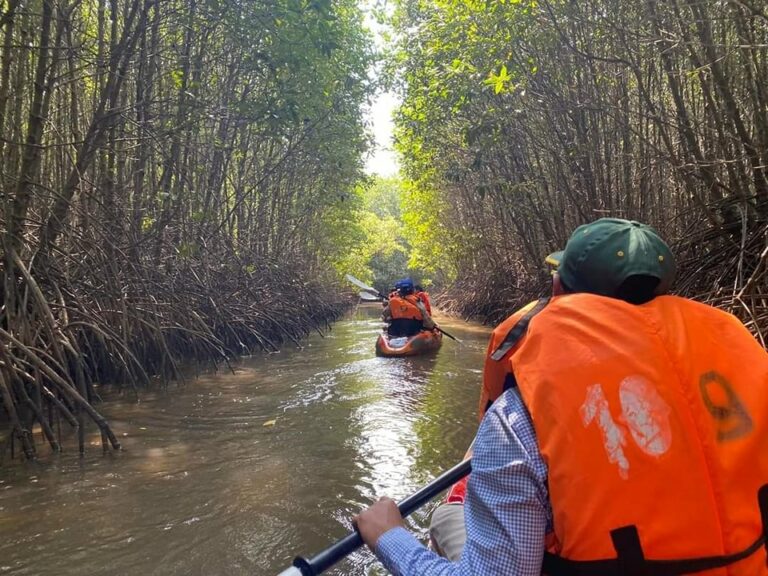

With most of our villages, we’re working with the Lao PDR Department of Forestry to assist villagers to harvest a cash crop out of the forests, to help them protect what they call “community forests”. We don’t want them to slash and burn to plant other crops; instead, we want villagers to see value in keeping the trees and then planting our coffee between them.

We work with the Lao PDR Department of Agriculture, Department of Forestry and local villagers to provide villagers a cash crop on on an incentive basis.

Today, it’s not a problem of us finding villages. It’s a problem of us having enough seedlings each year! There is a high demand from different villages that want to use our coffee, grow our coffee; there are also many villages that want to expand their current coffee crop.

You already have 80 villages that are growing your coffee, and you’re expecting to grow about 50 tons of green coffee in the coming years. How were you able to find a market for all of this?

The tourism industry in Laos is increasing parallel with Saffron Coffee’s business. Our product is high-quality, specialty-grade coffee. Having a local, high-quality product is very attractive to many hotels and cafes. Obviously we have our flagship cafe in Luang Prabang which by itself sells a lot of coffee, but we also provide to a lot of medium to high-end hotels, cafes and restaurants throughout Laos.

With an increase of coffee culture in Laos, along with an increase in tourism, we were able to sell out our whole crop every year.

Can you tell us about your flagship location in Luang Prabang?

We’re in a heritage house on the banks of the Mekong, about halfway down the peninsula from the royal palace to the end of the peninsula: a really lovely setting. Laos is known a little bit for coffee, but mostly from the south of Laos, and not many people know about northern Lao coffee.

In our cafe, we different coffee tastings and information tours for tourists, to help them know about projects that we’re doing, but also to let them know that northern Lao coffee is a thing that they should be aware of and support.

Can you tell me about the coffee that grows best in northern Laos?

We are growing Arabica; the Catimor or Typica varietals. The lowest elevation we have is 800 metres above sea level (masl) and the highest we have is about 1,300 masl at the moment. We buy the coffee off the villagers as cherries, and then we process it ourselves, we roast it. Or we export it as green bean.

We’ve had a few projects where we’ve set up processing plants in those villages and trained locals to process the coffee to parchment stage. And we buy the cherry off them, and then we pay them to process the parchment for us.

But for the majority, we’ll buy it as cherry, because that’s the part where we need to have strong control over, and villages usually have limited expertise and ability to do it. It’s much, much more worthwhile for us, in terms of economy of scale and for the villagers.

Are your export customers mostly within the Mekong Subregion? Or are you exporting your coffee further afield?

At the moment we have one consistent export client, which is Japan. We have demand from other countries, but we just can’t harvest enough at the moment. So we’ve kept our Japanese client because we’ve got a long term relationship with them, and we’ve sent off six tonnes of coffee to them this year. We do small-scale export to Thailand, but the majority of our coffee is sold domestically.

What effect has the pandemic had over your operations and sales?

The biggest impact COVID had on our market was on tourism from foreign sources coming into Laos, because most of their hotels, cafes and restaurants were our clients for our roasted coffee. They mostly shut down during the pandemic, because they didn’t have anyone coming into the country. That had a big impact on our on our bottom line.

At first in 2020, we were able to export coffee, prior to the container shortages hitting freight costs this year. We did look at selling coffee to America and Australia, but the quotes that we receive for that freight was astronomical because of the container shortages. That didn’t happen.

We’re expecting, in the coming years, that those prices will come down and export will be a bit better, particularly if we can get a direct export line from Laos through to destinations utilising the new train export service. We want to have a single point of departure for a whole container leaving Laos, rather than having a departure point in Thailand, because that adds a whole bunch of cost to us.

That’s also a very interesting point: the Laos high speed rail has opened new avenues for not just tourism but also export for businesses like Saffron Coffee.

That is the main reason why that was built; it wasn’t for tourist trains. It was for freight from inland China. We are yet to have an international port in Luang Prabang, but there is one in Vientiane. And so once we get to container load size, we will be able to utilise the international port and then ship through to anywhere in the world. In the future, when the train line eventually goes through to Bangkok in Thailand, we’ll be able to utilise that for those purposes.

What’s the value of sustainable community-based outreach projects like Saffron Coffee?

In the villages that we work with, we’ve definitely seen increases in the school leaving age of kids. Because the families are more secure financially, they can continue to send their kids to school for longer periods. That is one issue with Laos in terms of development, as the average age of school leaving is 12 or 13. That’s a major problem for development.

We’ve also seen that families are less likely to go into debt for medical issues and that sort of thing in our villages as well. Now, they’re not just hand-to-mouth farming, they actually have a sustainable income.